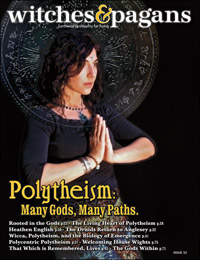

Hello, all! I have a new recurring column at Witches & Pagans Magazine! You can read the first post below, but from now on, you'll have to visit the magazine to see them.

Hello, all! I have a new recurring column at Witches & Pagans Magazine! You can read the first post below, but from now on, you'll have to visit the magazine to see them.In the next post, I’ll get to the meat of this blog, introducing you to a variety of lesser-known spirits from around the world and telling you the stories and teachings they tell to me. But I thought I’d start off by talking a little about mythopoesis as an art and a magical practice. The English word mythopoesis comes from the Greek μυθοποιία, and literally means “myth-making.” The second part of the word, “poeia,” is the root of our word “poet.” Historically, the word was an obscure technical term, describing, as Victorian historians would tell it, that period of time when humans made myths “instead of science” to explain the world around them. However, in 1931, J. R. R. Tolkien (author of The Lord of the Rings) published a poem titled Mythopoeia, which was a direct response to his frenemy and Oxford colleague C.S. Lewis’s skepticism about the value of myth. Lewis (at the time, although his views softened with the wisdom of age) believed that myths are "lies and therefore worthless, even though 'breathed through silver.”' Tolkien's poem replies...

“...

a star's a star, some matter in a ball

compelled to courses mathematical

amid the regimented, cold, Inane,

where destined atoms are each moment slain

...

[but] He sees no stars who does not see them first

of living silver made that sudden burst

to flame like flowers beneath the ancient song,

whose very echo after-music long

has since pursued. There is no firmament,

only a void, unless a jewelled tent

myth-woven and elf-patterned; and no earth,

unless the mother's womb whence all have birth.

...

[therefore] I will not treat your dusty path and flat,

denoting this and that by this and that,

your world immutable wherein no part

the little maker has with maker's art.

I bow not yet before the Iron Crown,

nor cast my own small golden sceptre down.”

Art by Aubrey Beardsley. from Le Morte d’Arthur (1893)

Like Tolkien, I believe that Creation is an ongoing affair, that moment by moment, word by word, we each breathe ideas into being. Tolkien writes “The incarnate mind, the tongue, and the tale are in our world coeval....in such 'fantasy,' as it is called, new form is made; Faerie begins; Man becomes a sub-creator." Tolkien, however, was still a male, nominally Christian, British aristocrat writing in the 1930s, and his view of the world, like our own, was heavily shaped by his lived experience of it. I write as an American feminist, Jew, witch, and all-around freak, and I go even further than he did: I say that the mythopoet, like the bard or the ovate, speaks for those who have tongues only of flame, and writes for those whose hands are the bare winter branches. For me, bardcraft and mythopoeia are an essential part of my relationship to the gods, the Land, the ancestors, and the World (both the Earth and the Other Places). It is my great hope that the stories and history I share with you here will help you root your practice as well.